Why we’re suing to fix elk management

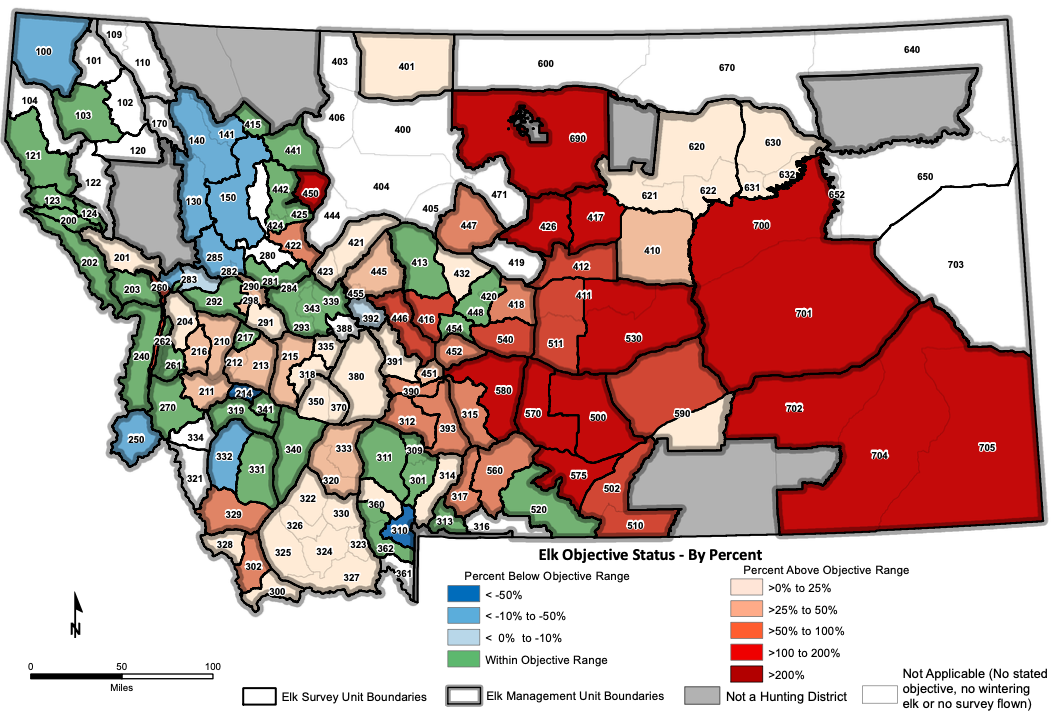

In a few areas of the state elk populations have been allowed to grow to crisis proportions. For example, in hunting district 417 in Fergus County, the elk population is estimated at 4,300 animals—that’s eleven and a half times more than the sustainable population objective set by state wildlife biologists.

Excessive elk populations have caused an untenable hardship for the ranchers who provide habitat. This is an area suffering from extreme drought, grasshoppers, and wildfire in recent years. Many cattle producers last year reduced their mother cow herds by 25 percent or more. BLM has notified ranchers in this area of a 30 percent reduction in AUMs for this year due to a shortage of grass.

These difficulties are compounded by elk populations grown wildly beyond what is considered sustainable as those elk damage crops, attack hay yards, and compete for forage.

The causal factor that has led to this elk population crisis is the policy of the Fish and Game Commission. In 2007 they designated hunting district 417 and a dozen other districts as special “trophy” districts and strictly limited hunting opportunity. In HD 417, the Commission allows only 225 either-sex elk rifle permits and 300 archery permits. With such restrictive opportunity, it’s no wonder the population has exploded beyond sustainability.

Ranchers in hunting district 417 have appealed for assistance for years. In 2020 and again in 2021 they filed petitions with the Commission asking for expanded hunting opportunity—and in both cases those ranchers were ignored.

This year relief was in sight when the Department of Fish Wildlife and Parks recommended the Commission issue unlimited archery permits and increase the number of rifle permits by 50 percent for these over-objective, limited-permit districts. But in a last-minute reversal the Commission rejected the Department’s recommendation. Instead, the Commission reduced the number of archery permits for 417 by about 100 for the 2022 hunting season.

The Commission’s decision goes beyond bad policy—it’s against the law. The Commission is required to set a population objective for each hunting district based on habitat and landowner tolerance, and then to implement management policy that maintains a population at or near that objective. When populations exceed objective levels, the law requires them to implement “liberalized harvests, game damage hunts, (and) landowner permits,” and to relocate animals. They haven’t done this—in fact they’ve done the opposite.

This is why we are suing the Commission. They have callously ignored their statutory duty for years and created a problem that is causing increasing damage to ranchers. They’ve singled out some areas—mostly in Eastern Montana—for trophy hunting, which unfairly requires limiting hunting opportunity. Our lawsuit seeks a change in policy at the Commission to bring populations levels down to where the law says they’re supposed to be and to establish consistent management statewide. You can read our complaint here.

Montana ranchers are generous people, and they love the land and the wildlife it sustains. But in exchange for providing that habitat the state needs to hold up its end of the bargain by managing big game in a way that keeps the burden of sustaining wildlife at a reasonable level.

The solution is not to throw open the gates to unlimited access by the public on private land—that only increases the burden on landowners. We already have the solutions at hand—they’re spelled out in the law and in the elk management plan. We just need the Department and the Commission to follow their own policy. Ranchers in these hunting districts have reached the breaking point—if the Commission won’t provide relief then it’s up to the courts to compel them to do so.